Our Industry

In the March 1942 issue of the journal Modern Hospital, Charles F. Neergaard, a prominent New York City hospital design consultant, published a layout for a hospital inpatient department that was so innovative he copyrighted it. For each unit, a corridor provided access to a row of small patient rooms along a long exterior wall and to a shared service area between the two corridors.

The feature that made his plan so innovative—and therefore risky? It included rooms that had no windows.

A windowless room hardly seems daringly innovative nowadays, but in the 1940s it was a shocking proposal for a patient wing. It violated a long-lived understanding of what, exactly, the role of the hospital building should be in terms of promoting health.

With the development of germ theory, sunlight and fresh air had new purposes. Experiments proved that ultraviolet light was germicidal. So, windows of clear glass, or even of special "vita-glass" that did not block the UV rays, were a means of surface decontamination.

Similarly, tuberculosis sanatoria records proved that simple exposure to fresh air could be curative. The hospital building itself was a form of therapy. In a 1940 issue of the architectural journal Pencil Points, Talbot F. Hamlin confidently noted that "the quality of the surroundings of the sick person may be as important in the cure as the specific therapeutic measures themselves."

The feature that made his plan so innovative—and therefore risky? It included rooms that had no windows.

A windowless room hardly seems daringly innovative nowadays, but in the 1940s it was a shocking proposal for a patient wing. It violated a long-lived understanding of what, exactly, the role of the hospital building should be in terms of promoting health.

With the development of germ theory, sunlight and fresh air had new purposes. Experiments proved that ultraviolet light was germicidal. So, windows of clear glass, or even of special "vita-glass" that did not block the UV rays, were a means of surface decontamination.

Similarly, tuberculosis sanatoria records proved that simple exposure to fresh air could be curative. The hospital building itself was a form of therapy. In a 1940 issue of the architectural journal Pencil Points, Talbot F. Hamlin confidently noted that "the quality of the surroundings of the sick person may be as important in the cure as the specific therapeutic measures themselves."

In order to provide a window in every room, buildings could not be wider than two rooms deep; this inevitably required multiple long narrow wings. Such rambling structures were expensive to build, prohibitively expensive to heat, light, and supply with water, and inefficient and labour-intensive to operate. Food reached the patients cold after being trucked from a distant central kitchen; patients requiring operations were wheeled through numerous buildings to the surgical suite.

Hospital designers thus began to arrange practitioners, spaces, and equipment into a more effective layout. Catchwords changed from "light" and "air" to "efficiency" and "flexibility." An emphasis on efficiency rapidly took over the utilitarian areas of the hospital; time and motion studies determined layouts and locations of kitchens, laundry, and central sterile supplies. Diagnostic and treatment spaces were re-designed to establish efficient, but aseptically safe, paths for the movement of patients, nurses, technicians, and supplies.

By the 1950s, with the advent of antibiotics and improved aseptic practices, the medical establishment also believed that patient healthiness could be maintained regardless of room design. Some doctors even preferred the total environmental control offered by air conditioning, central heating, and electric lighting. Windows were no longer necessary to healthy hospitals, and by the 1960s and 1970s even windowless patient rooms appeared.

Hospital designers thus began to arrange practitioners, spaces, and equipment into a more effective layout. Catchwords changed from "light" and "air" to "efficiency" and "flexibility." An emphasis on efficiency rapidly took over the utilitarian areas of the hospital; time and motion studies determined layouts and locations of kitchens, laundry, and central sterile supplies. Diagnostic and treatment spaces were re-designed to establish efficient, but aseptically safe, paths for the movement of patients, nurses, technicians, and supplies.

By the 1950s, with the advent of antibiotics and improved aseptic practices, the medical establishment also believed that patient healthiness could be maintained regardless of room design. Some doctors even preferred the total environmental control offered by air conditioning, central heating, and electric lighting. Windows were no longer necessary to healthy hospitals, and by the 1960s and 1970s even windowless patient rooms appeared.

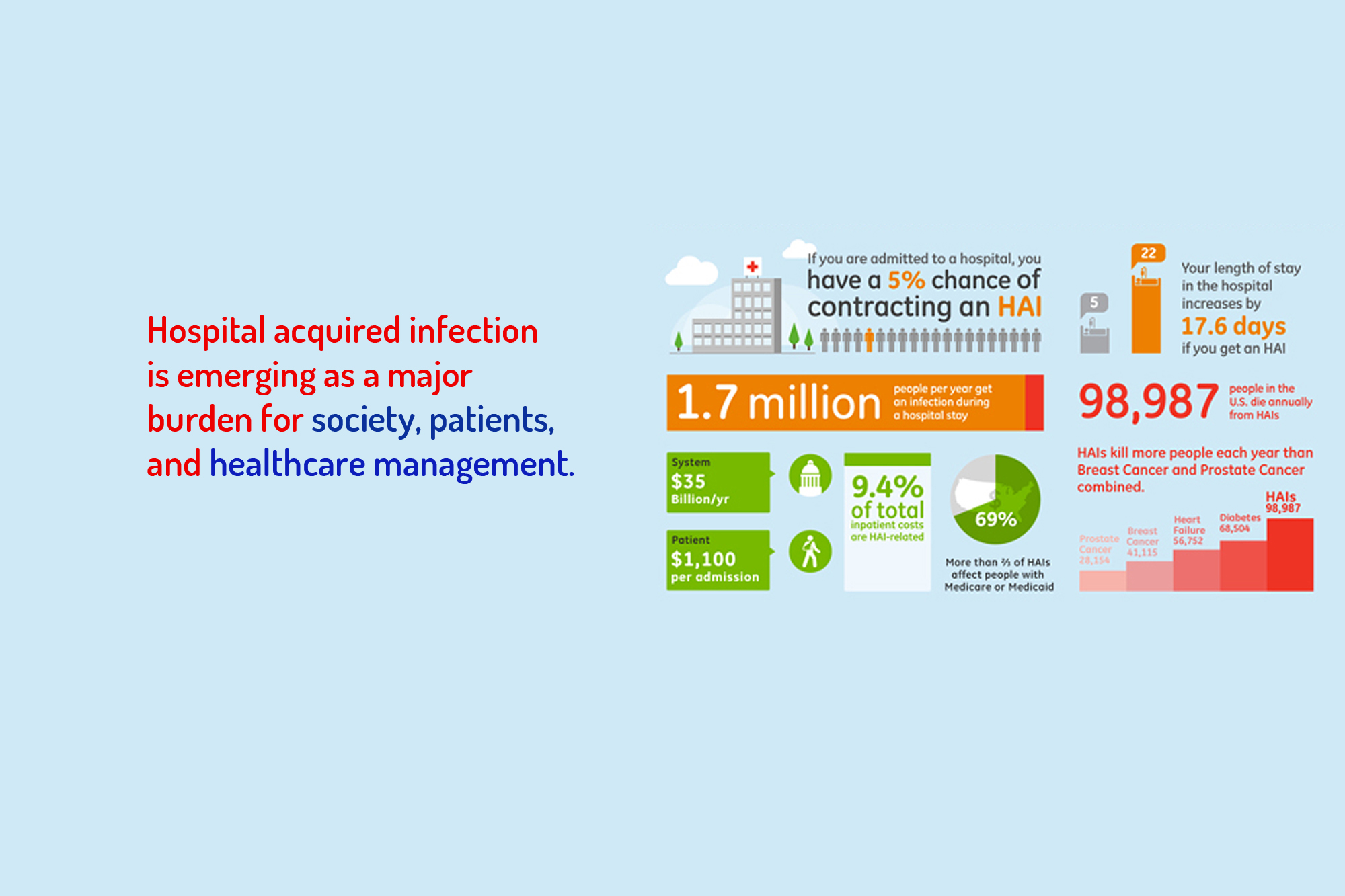

Present HVAC systems have control of microbes by installation of HEPA in the air intake duct but precisely no control of particulates and microbes entering the hospital by human traffic inflow pathway or for the matter the microbes generated/released during procedures or by inpatients. While OTs resorted to fumigation at day/week end to supposedly kill the airborne microbes, its efficacy in doubt. Nothing much is being done to eliminate microbes in the air in the ICUs, special wards or for the matter in all the other areas of the hospital.

We have most of the old hospitals having stand-alone air-conditioners fixed instead of the HVAC system. The greenfield projects and new additional buildings nowadays are being built with the HVAC system. In the brownfield projects addition of HVAC system is becoming a challenge due to severe modifications required to the existing structures, hence only air conditioners are being fixed for the OTs and ICUs and the day-to-day functioning is being carried out. Airborne microbes and air borne pollutant control is thus becoming a big challenge.

We have most of the old hospitals having stand-alone air-conditioners fixed instead of the HVAC system. The greenfield projects and new additional buildings nowadays are being built with the HVAC system. In the brownfield projects addition of HVAC system is becoming a challenge due to severe modifications required to the existing structures, hence only air conditioners are being fixed for the OTs and ICUs and the day-to-day functioning is being carried out. Airborne microbes and air borne pollutant control is thus becoming a big challenge.

About Us

Quinton AOM, a fully integrated air solutions company headquartered in Mumbai, India has been set up by a team of technocrats led by Moloy Chakravorty who believe that the benefits of clean and healthy air not only enhances quality of life, but also increases work productivity.

Team Quinton believes the benefits of clean and healthy air not only enhances quality of life, but also increases work...

@2018 Quinton AOM Air and Odor Management . All rights reserved.

Site by Bitsinbin